The Battle for Buddha Gaya

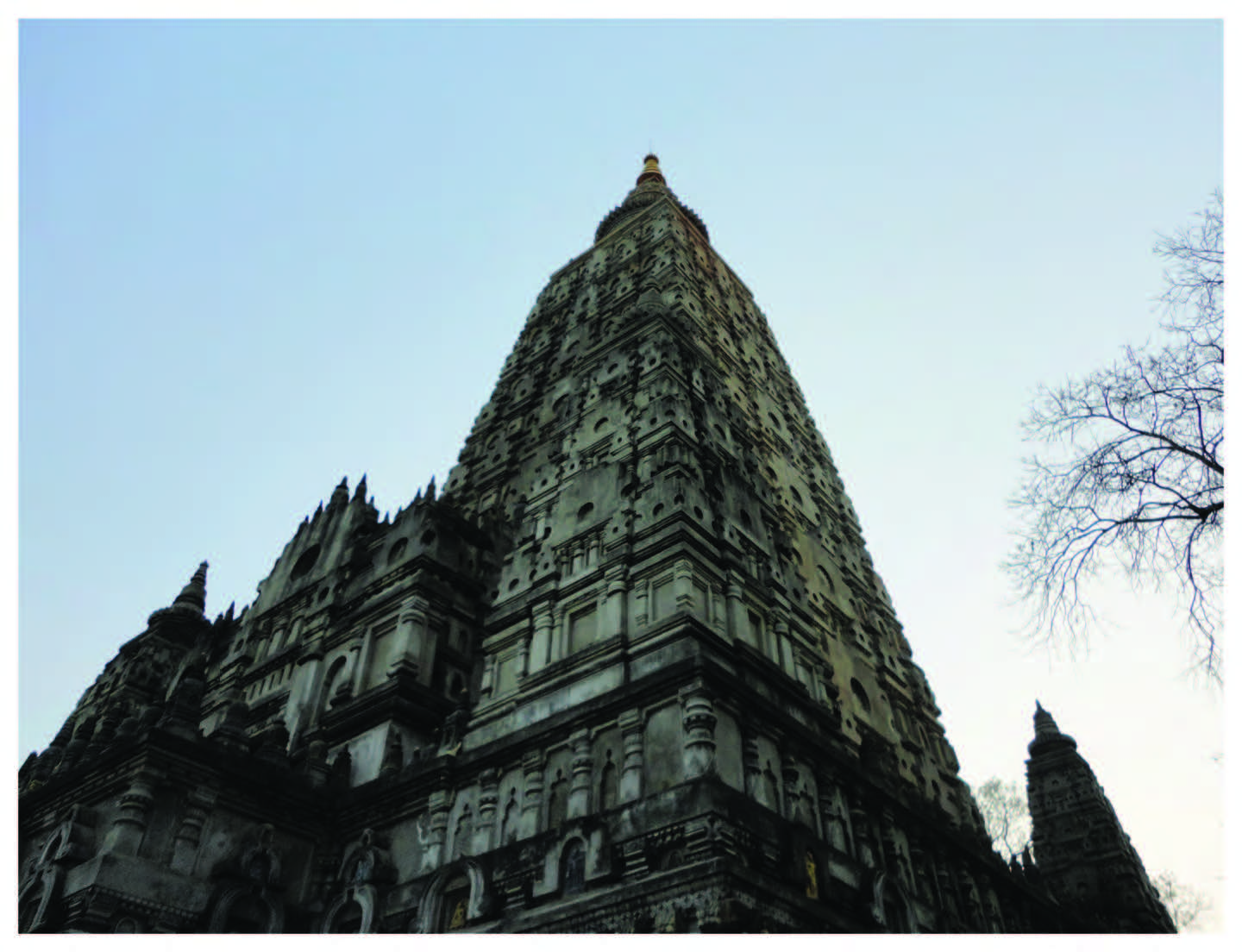

A few kilometers from the city of Gaya in the North Eastern Indian state of Bihar is Bodh Gaya, or Buddha Gaya, so named because it is here that Siddhartha Gautama, the son of King Suddhodana, having renounced his princely life, became an ascetic and attained enlightenment or "Buddhahood" after years of meditation. To the estimated 300 million Buddhists around the world, this is the holiest of holy sites.

For Anagarika Dharmapala, Buddha Gaya was a battle cry, a life's mission that began when he was in his 20s.

Over the centuries since the Buddha's passing away, a temple built by King (later Emperor) Ashoka in veneration of the Buddha had fallen into neglect. A powerful local 'Mahant' (Hindu religious man) had taken possession of the holy site. Dharmapala referred to Buddha Gaya as the "Buddhist Jerusalem", a place that is to Buddhists what Zion is to the followers of Judaism, and Mecca to the followers of Islam.

Ironic as it was, it is due to the British colonial administrators that Buddha Gaya was rediscovered. It was the discovery of Buddhist sites in India that excited the young Dharmapala and drew his interest towards Buddha Gaya.

In the early part of the 19th century (1809), a Scottish surgeon, Francis Buchanan had rediscovered Buddha Gaya. He had mentioned the existence of Hindu and Buddhist artefacts in the area. But it was only towards the latter part of the same century that British archaeologists, headed by Alexander Cunningham, a British army engineer, rediscovered a 'Buddhist India'. These archaeologists had mapped out these sites and based their findings from the writings of Chinese pilgrim travellers of a by-gone era, Fa-hien and Hsuan Tsang, whose writings had been translated to European languages. The colonial Government started an archaeological survey of India and began excavations at Taxila, Nalanda, Sarnath, Sanchi, Lumbini and Buddha Gaya. They unearthed sufficient material to prove the impact of Buddhism in ancient India. Much of that history had been discovered earlier by the Indian King (later Emperor) Ashoka, before the colonization of India, but had gone into the limbo of forgotten things as Hinduism and Islam competed for dominance in the pre-colonial era of the country.

The rediscovery of Buddha Gaya by Cunnigham, and about the same time, a breathtaking poem, The Light of Asia on the life of the Buddha, by an English journalist, Sir Edwin Arnold, following a visit to Buddha Gaya, jolted the young Dharmapala, who was then active as a member of the Theosophist Movement. The poem brought tears to his eyes, he said later. He got up from his bed at 'Victor House' in Colombo (now the Dharmapala Girls school) and made a hasty journey to the holy site across the Palk Straits, the narrow strip of sea that divides then Ceylon with India. He took with him two Japanese monks, Ven. Kozen Gunarathana and Tokuzawa who had come to Ceylon after his visit to Japan with Olcott earlier. They arrived at Buddha Gaya via Madras (now Chennai), Bombay (now Mumbai) and Benares on 22 January, 1891.

When Dharmapala visited Bodh Gaya, the Ashokan temple was poorly maintained. Both Hindus and Buddhists worshipped at the site, but in small numbers. The King of Burma (now Myanmar) was largely responsible for the Buddhists' interest as his countrymen would visit from reasonably close proximity to pay homage to the Buddha. A few Tibetan Buddhists would also arrive from time to time. There was a Burmese pilgrims rest nearby. The control of the temple however remained with the Hindu Mahant, who had a palatial residence in the next block of land. He allowed Buddhists to visit the temple.

Taken aback with what he saw; a neglected and dilapidated temple of the holiest of holy sites of the Buddhists in the hands of a Hindu priest, Dharmapala took a vow by the tree under which Buddha had meditated, (or a sapling from the original tree), to direct all his energies to regain control of the ownership and management of Buddha Gaya to the hands of the Buddhists.

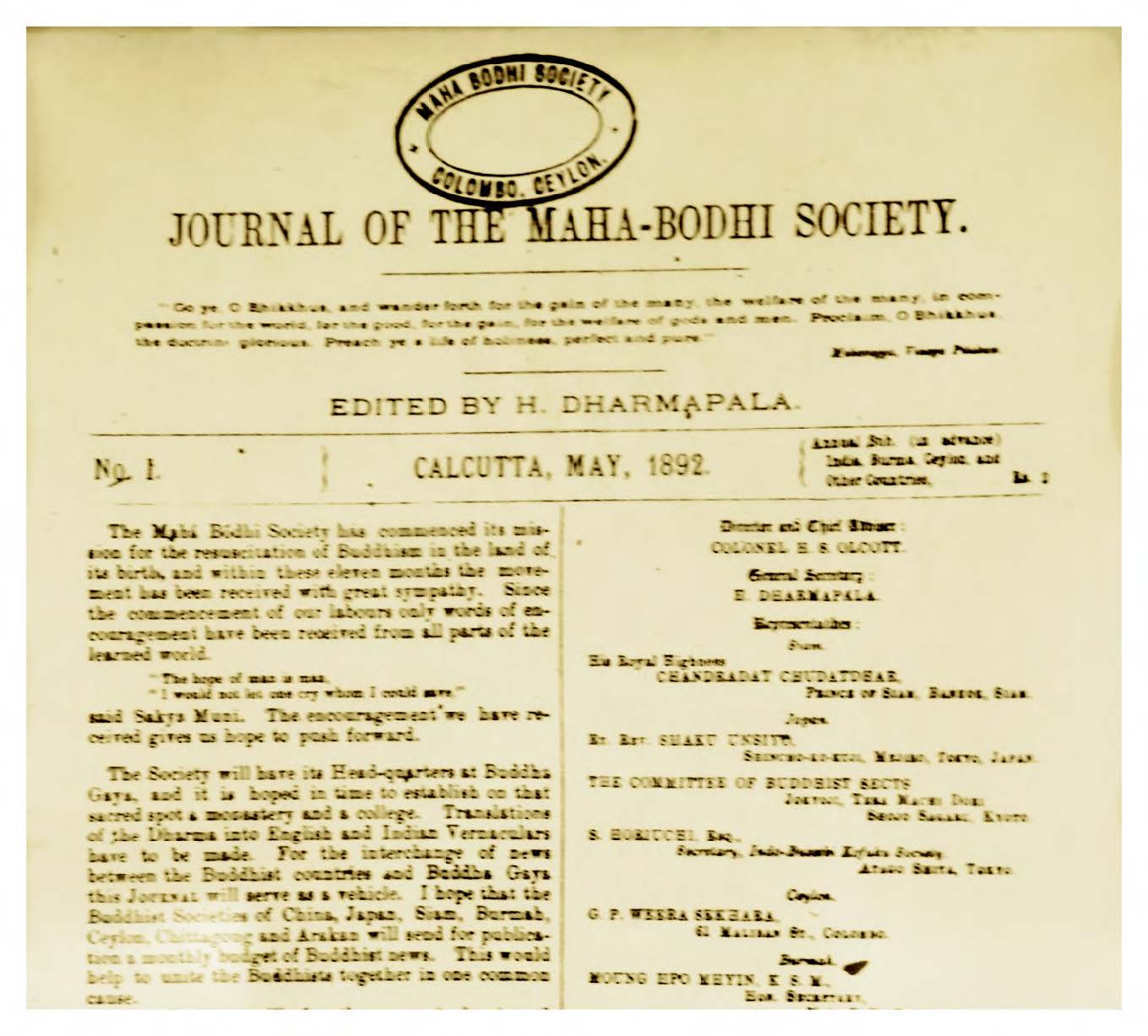

As the Buddha is an avatar of Vishnu in the pantheon of Hindu Gods, Hindus also venerated the Buddha and made offerings to the Buddha statue at the temple. But the Buddha was dressed as a Hindu God wrapped in a cloth and more ominously, with a 'tilak' or a round marking placed on the forehead as Hindus customarily do. "It seemed an outrage that this holiest temple of the Buddhists should be under the management of a man whose ancestors had always been hostile to Buddhism," Dharmapala penned in an essay; Memories of an interpreter of Buddhism to the present-day world, written twenty six years after his first journey to Buddha Gaya in 1891. On his return to Ceylon, Dharmapala launched the Maha Bodhi Society the same year to liberate Buddha Gaya from Hindu control. In his stentorian voice he went round Ceylon (Sri Lanka) with the call "Sinhalayeni Nagitiyaw. Buddha Gaya-wa bera ganew" ('Wake up you sleepy Sinhalese - save Buddha Gaya'). He sent four Buddhist monks to Buddha Gaya to take up residence at the Burmese pilgrims’ rest.

Dharmapala went back to Buddha Gaya after forming the Maha Bodhi Society. As he embarked on what was to become a relentless campaign, he attracted physical violence towards him when the group he had with him on this second visit tried to go to the upper floor of the temple and place a Buddha statue he had brought with him from Japan. The Mahant's workers attacked them for 'intruding'.

For obstructing the little ceremony, Dharmapala took the Mahant and his servants to Court. Thus, began what came to be known as 'The Great Case'. English lawyers appeared for both parties. The English District Magistrate held with Dharmapala. The Mahant's employees were found guilty of unlawful assembly. In delivering his order, the Magistrate referred to the "essentially Buddhist character of the temple". The first salvo had been fired in the battle for Buddha Gaya. The Mahant appealed against the convictions to the District Collector, also an Englishman and lost again. He then appealed to the Calcutta High Court where an Englishman and a Bengali judge sat.

The Calcutta High Court eventually held against Dharmapala and set aside the convictions of Mahant's employees. The judgment meant that the British Colonial Government held the ownership rights to the temple, and the Mahant had the managerial rights. Undeterred, Dharmapala took the next best step, to purchase property around the temple from the Mahant. The Mahant refused the offer. Dharmapala then purchased land in Gaya, a few kilometers away. Like in Calcutta and Sarnath, he was establishing legal claims for Buddhist ownership of land in India.

Dharmapala was to engage in multifarious projects throughout this period of litigation for control of Buddha Gaya, but he never lost the stomach to continue the good fight for control of the temple. From wherever he was, he lobbied influential personalities of that era. He wrote to the British Viceroy, intellectuals in Europe and America, Indian sympathisers, including the national freedom fighters of the time. He had the support of the Bengali elite in Calcutta, then the seat of colonial India's capital. The newly-formed Maha Bodhi Society meanwhile, galvanized the support of Royalty in Thailand, and in Japan to the cause. A mass movement in Ceylon under the banner of the Maha Bodhi Society was demanding the rights of the Buddhists in India. Buddha Gaya was made into the symbol of international Buddhism with worldwide agitation for the managerial control of the temple.

Dharmapala then went West in the 1920s and took Buddhism to that part of the world where the Dhamma was being studied by a few scholars, but nothing more. The foundation for the control of Buddha Gaya for the Buddhists had however been laid. He had implanted the seed of righteousness and the justifiable demand of the Buddhists for Buddha Gaya among the next crop of India's leaders, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad and B. R. Ambedkar, among others.

Becoming a Buddhist monk in the evening of his life and with the Battle for Buddha Gaya behind him, Dharmapala asked the Maha Bodhi Society he had formed to carry forward the baton. Dharmapala passed away in 1933 with India still under colonial rule and the “Buddha Gaya Question” unresolved. But the inexorable demand that he had set in motion was duly followed up after his death by the Maha Bodhi Society.

Two years after Independence from British colonial rule, the free Indian Government introduced the Bodh Gaya Temple Act of 1949 passing the ownership of the Buddha Gaya temple to the state Government of Bihar and the management of the temple to be shared equally by the Hindus and Buddhists in a Joint Committee with the District Magistrate as the Chairman, even if he be a non-Hindu.

In 1978, the then President of Sri Lanka, J. R. Jayewardene, opened the main street leading to the Maha Bodhi temple named after Anagarika Dharmapala. UNESCO declared Buddha Gaya as a World Heritage site in 2002.

There is a Maha Bodhi Society building now with resident monks and a pilgrims’ rest within walking distance to the main temple that was the bone of contention at the turn of the 20th century. Buddhist temples and rests from Buddhist countries are housed in close proximity to the main Maha Bodhi Vihara.

The Government of India recently opened an international airport at Buddha Gaya to accommodate the many thousands of Buddhist pilgrims who come from all over the world to pay homage to the Buddha.